ResourcesArticle

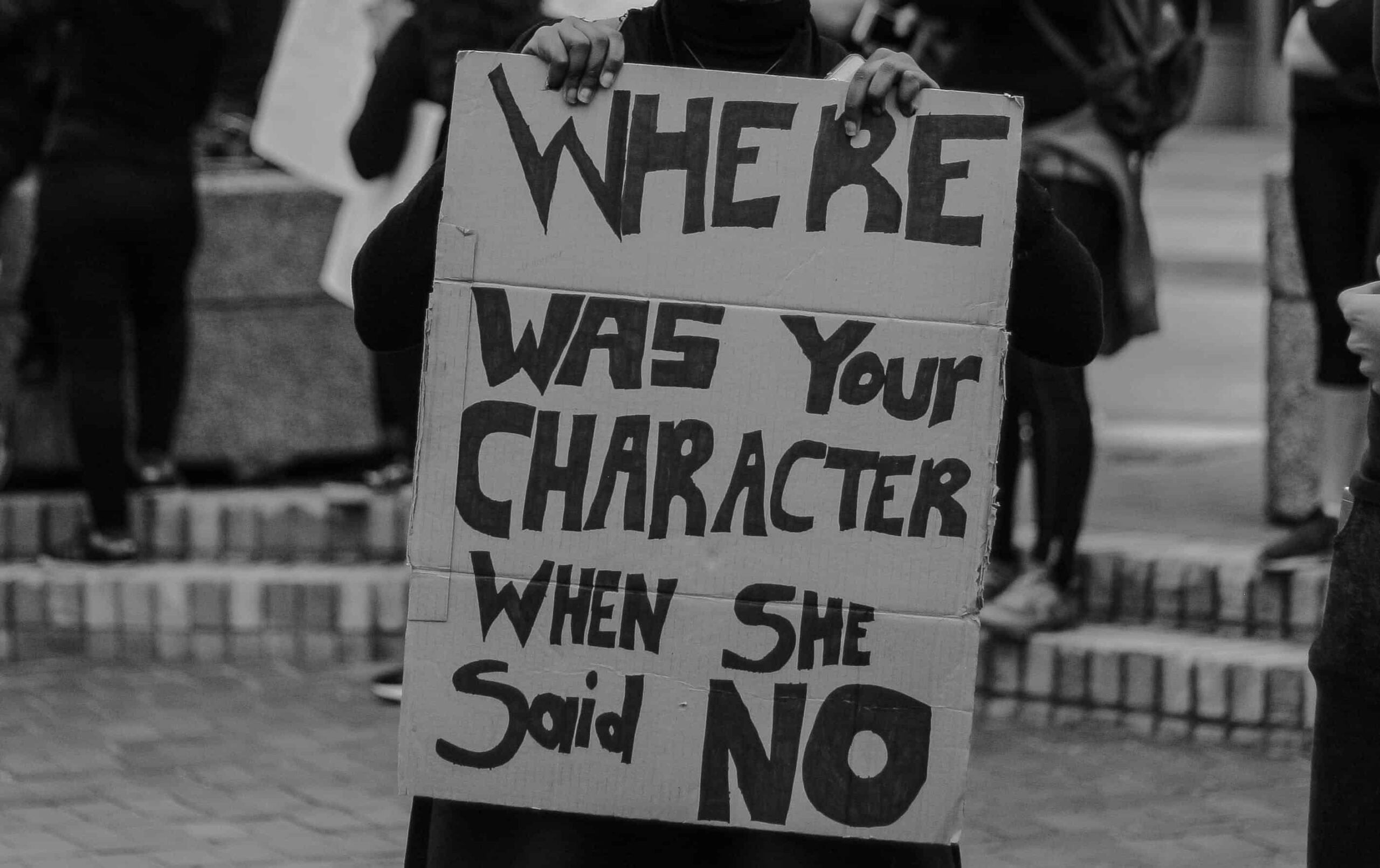

Spotlighting Victims, Omitting Perpetrators: How GBV Discourse Gets It Wrong

![]() 3rd January 2024

3rd January 2024

DESCRIPTION: AN ARTICLE CRITIQUING GBV DISCOURSE THAT FAILS TO HOLD PERPETRATORS ACCOUNTABLE

This article discusses explicit case law pertaining to rape. Readers are urged to take into account their mental wellbeing before reading further. Please access TCR’s wellness resources or get in touch with our affiliate trauma therapists, if needed.

In 1972, two policemen in Maharasthra, Tukaram and Ganpat, committed a custodial rape against a tribal child. The case, which culminated in the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1983, was defined by three judgments:

- The first, by the sessions court, found defendants not guilty in a verdict that stated that the child was “used to having sex” and therefore, must have consented.

- The second, by the Bombay High Court overturned this judgement, emphasising that the child’s appellants were strangers, which made it unlikely that she would have willingly engaged in sexual intercourse with them.

- The third, by the Supreme Court, eventually acquitted the accused on the grounds that there was no proof that she resisted, thereby proving her consent.

Commonly, the first and the third judgements are criticised for their explicit misogyny while the second is praised for its contribution to jurisprudence about passive submission versus consent. It goes unnoticed that all three judgments have one thing in common; they focussed solely on the victim’s behaviour, placing on her the entire onus of proving the absence or presence of consent.

What of the perpetrators, Tukaram and Ganpat? Five decades since the rape, they fade into obscurity. The Tukaram and Others vs. State of Maharashtra case, like all prominent cases of sexual violence, remains better known today by the name of the victim: Mathura. The rape, the legal battle, and the eventual victories it gained in advancing women’s rights are all part of the child-victims’ legacy.

From case law to media reportage, discourse about gender-based violence (hereafter, GBV) is marked by the two paradigms made apparent here. First, all victims must be women. Legal, sociological, and psychological interventions pertaining to GBV are often gender-specific and exclude the possibility of victims identifying with other genders. As a result, children like Mathura (specially before the POCSO Act of 2013), and non-binary or trans people are often only considered victims when womanhood can be imposed upon them. Second, all violence is about the victim. Data, interventions, and general discourse tend to over-focus on victims while perpetrators fade into obscuration.

The cumulative result of this is that all gender-based violence (including sexual violence) is synonymous with the victimisation of women. This is ‘violence against women,’ a term used abundantly by researchers, scholars, activists, social workers and legal professionals alike, which views GBV as the violence that mostly women endure, not the violence that mostly men perpetrate.

Why are Perpetrators Obscured? A History

Why is it that discourse surrounding GBV and sexual violence tends to overemphasise the positioning of victims and survivors while obscuring the perpetrator? The roots of this lie in 17th century England where jurist Matthew Hale’s ‘warning’ about rape cases: that they are easy to make, hard to prove, and harder yet to be disproved by innocent parties. In line with this logic, Hale placed emphasis on the character of rape victims, her history of consenting to sex, the presence of clear physical proof of violation, and on the promptness of the rape complaint. History does not support the claim made by a man most well-known for his treatise defending marital rape exemption in common law, but the rhetoric remains a common defence strategy, with Hale’s writings being cited in court till as recently as the judgement to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Susan Estrich wrote, “an inquiry into the victim’s nonconsent puts the woman, not the man, on trial.” That is to say, the point of inquiry is whether the survivor-victim consented, not whether the perpetrator took consent. The latter would require an assessment of the perpetrator’s character, their history of past violations, and the presence of clear physical proof that there was consent (“well that’s ridiculous!” says a reader accustomed to the opposite being demanded of survivor-victims in courtrooms).

In British colonies like India, the central tenets of Hale’s legal philosophy were amplified. Dr. Norman Chevers, the author of India’s first publication on medical jurisprudence wrote that the “deceit inherent in the character of the lower class of natives” made it necessary to set higher standards for medical evidence permissible to prove rape in India than those in Europe. He argued that in cases of rape, victims should be given no notice of the medical jurist’s intent to perform an examination to prevent them from preparing from it, that doctors should take into account prior sexual history and the ability of the victim to have self-inflicted injuries incurred during rape, and that women of certain castes were more likely to make false allegations.

Media Reports of GBV

Even today, the over-emphasis on victims’ behaviour in cases of GBV is not a pattern limited to case law and judicial practice. A cursory google search for news articles relating to the phrase “gender based violence Delhi” yields the following results:

- An article by The Hindu (dated 4th Dec 2023) titled, “Highest Cases of Sexual Violence Make Delhi Most Unsafe for Women.”

- An article by The Wire (dated 28th Nov 2023) titled, “A Third of Women Worldwide Experience Physical or Sexual Violence During Their Lifetime: WHO.”

The first article begins by sharing the following statistics; that Delhi recorded 14,158 incidents of crime against women in 2022, with about 186.9 crimes reported for every 1,00,000 women. The second article also states that around 33% of women worldwide experience physical or sexual violence.

The first article continues, describing measures taken by law enforcement to mitigate sexual violence. A senior police officer stated, “we do carry out awareness drives to explain…what to do when women and girls find themselves in such situations.” Of course, an argument can (and should) be made that reforming the victims instead of perpetrators of a crime is not an effective strategy for mitigation. However, to think through perpetrator rehabilitation, it is first important to affirm the presence of a perpetrator at all. That sexual violence is a situation women “find themselves in” makes sexual violence appear to be a perpetrator-less crime.

The article by The Wire expands upon data about the effects of such violence on women survivor-victims. Women incur higher costs, including expenses to support their medical needs, emotional well-being, and disruptions to education or employment. Women who ‘experience’ sexual violence earn 60% lower than women who do not experience such violence. What about men who perpetrate sexual violence? Do they economically benefit from causing such violence in contrast with men who don’t? The use of passive voice in media reportage shapes a perspective of GBV research that does not know how to start to ask such questions.

So we wind up with detailed statistics of how many women, which women, in which cities, in what settings, are “experiencing” sexual violence, almost as if they “experience” it spontaneously, making it a perpetrator-less crime. 1 in 5 women in America’s university campuses, 186.9 in a 1,00,000 women in Delhi, 33% women worldwide, but what do we know of the perpetrators? How many men commit sexual violence? Where, how, and why do they perpetrate sexual violence? Statistical data about sexual violence, just like case judgements, focus disproportionately on women survivor-victims instead of men perpetrators. To start the process of collecting perpetrator-focussed statistics, language about GBV first needs to make apparent the presence of a perpetrator at all.

‘Violence by Men’

Reorienting the victim-focussed perception of GBV research requires a rethinking of linguistic categories. The wide acceptance of the term ‘violence against women’ obscures not only GBV and sexual violence against victims that may belong to any other gender but also naturalises the presence of violence in women’s lives: to be a woman is to face violence from seemingly unidentifiable or unnamable perpetrators. It is acceptable to state that it is mostly women who endure GBV but provocative to assert that it is mostly men who perpetrate it. This is despite the fact that perpetrators tend to be mostly male regardless of whether victims are queer, male, or female.

The term ‘violence by men,’ just like the term ‘violence against women’ obscures many forms of GBV and sexual violence. Just as the former obscures GBV with women or non-binary perpetrators, the latter obscures GBV where victims are male or non-binary. At the end of the day, it is the term ‘gender-based violence’ that makes most room for an exploration of the gender-related dimensions of violence, provided that the term ‘gender’ is not used as a synonym for ‘women.’ Still, the term ‘violence by men’ retains more statistical and sociological accuracy than ‘violence against women.’

The goal is to provoke a starting point for reorienting interventions against GBV to focus on perpetrator behaviour, and seek to rehabilitate masculinity instead of burdening women with the onus of defence.

References

Baxi, P. “Sexual Violence and Its Discontents.” Annual Review of Anthropology 43 (2014):139-154.

Estrich, Susan. “Rape.” The Yale Law Journal 95, no. 6 (1986): 1087–1184. https://doi.org/10.2307/796522.

Kolsky, Elizabeth. “The Body Evidencing the Crime: Rape on Trial in Colonial India, 1860-1947.” Gender & History 22, no. 1: 110-114.